A report published this week shows that domestic abuse perpetrated by police officers is still all too common. This article references domestic and sexual abuse.

Lorraine* was young when she met her ex-boyfriend through her first policing job in 2004 – just 20 years old. Thomas* was older, more experienced in the force and immensely charming. She quickly learnt that his charm could come and go like a flash of lightning. During their five-year relationship, Thomas isolated Lorraine from her family, abused her physically and psychologically and raped her multiple times.

“I was forced into a number of sexual things,” Lorraine says, explaining this included sex with other men – something she never felt comfortable with. “I did the things that he requested of me, and then I’d be met with a barrage of abuse from him.”

A colleague noticed Lorraine’s bruises and encouraged her to report Thomas. But the criminal investigation dragged on and eventually went nowhere. Her career in the force suffered as Thomas continued to intimidate her at work. He, meanwhile, was promoted.

A report published this week by the Centre for Women’s Justice shows that domestic abuse perpetrated by police officers is all too common. Little progress has been made since the legal charity filed a super-complaint on this issue in 2020.

The report outlines that over 200 women have come forward since 2020, sharing their experiences of abuse by police officers. It finds that there’s a continued failure within police forces to properly investigate and document allegations against officers, and that coercive behaviour is often brushed off as “unpleasant but not criminal.”

As part of the report, the Bureau for Investigative Journalists sent freedom of information requests to all police forces in England and Wales covering the period between 2017 and 2022. Their findings show that over half of all forces employed at least one police officer with multiple sexual offence allegations. It’s clear that it’s common for repeat allegations to go unconnected, or dismissed.

When it came to serving Metropolitan police officer Wayne Couzens, this lack of connecting the dots ultimately left him free to abuse his position. In 2021, he kidnapped and murdered Sarah Everard as she walked home.

It was Everard’s murder that encouraged Lorraine to re-report Thomas’s abuse in 2021, many years after her initial report was shut down. By then, she’d realised there had been multiple worrying allegations against Thomas over the years.

Following Couzens’ arrest, Lorraine’s force had set up a unit to encourage culture change, so she felt more confident to re-report her concerns. She now thinks that she was naive to expect a fast and rigorous response. The investigation dragged on for almost three years.

Thomas was eventually found to have committed gross misconduct and would have been dismissed. However, the length of the investigation meant he’d had time to resign and secure a good job outside of the police.

To better understand why such serious abuse allegations don’t get investigated thoroughly, I spoke to Dr Natasha Mulvihill, an Associate Professor in Criminology at Bristol University who has co-authored work on police-perpetrated domestic abuse.

She explains that there’s a lack of processes to ensure reports against an officer are investigated independently.

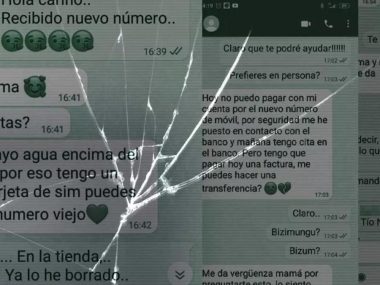

“We’ve heard of investigations being managed by colleagues of the perpetrator, who were also their friends or acquaintances socially,” Dr Mulvihill recalls. “One woman we spoke to told us how much courage it had taken her to finally call and report her partner. As soon as she walked back into the kitchen, he asked her why she’d reported him. His boss had tipped him off that she’d called the police.”

My stomach turns after hearing this, as I recall my time as a domestic abuse advocate. When speaking to survivors of abuse, I’d emphasise how important it was to keep their disclosures and plans a secret. This is because any attempt at escape or intervention can set an abuser off, escalating the situation.

Dr Mulvihill explains that the level of access that abusive officers have is what makes them so dangerous:

“Police officers have the freedom to move across public and private spaces in a way that is unusual. They have training in restraint, they know the law. They know all about evidence gathering. They know where women’s refuges are. They can look up addresses and number plates. They have extraordinary access to resources.”

Worryingly, some officers with abuse allegations against them work in roles where they investigate domestic or sexual abuse. Others work in child protection. This warrants the question of whether policing attracts unsavoury characters, aiming to abuse their position.

“I think so, yes,” Paula, a retired police officer, agrees when I pose this question to her. “They put the uniform on, and all of a sudden they have that power.” Paula met her police officer ex-partner at work. Paula and her ex were already retired and had broken up when he assaulted her.

The officers attending the scene had worked closely with Paula’s ex. Despite her serious injuries and evidence given from an eye witness, the police dismissed Paula’s report, treating her as the guilty party.

“He made a lot of malicious allegations against me, and they took priority. I was interviewed in the police station cell block for those alleged offences. It took me three years to clear my name from that and to establish that he had lied.” By then, it was too late for a charge to be brought for the assault.

The sexist and racist culture within policing has come under fire in recent years. Many of the experts and insiders I spoke to believe that these concerns are not being taken seriously enough.

Harriet Wistrich, Director of the Centre for Women’s Justice, assures me that there’s no shortage of potential solutions to police perpetrated domestic abuse: from better vetting standards and data collection when allegations arise, to ensuring abuse from a police officer is investigated independently.

However, she believes that nothing short of rooting out “entrenched cultures that are resistant to change” and making “energetic interventions” will ensure lasting change. Otherwise, she warns: “we’re just going to see more abuse, more abusers getting away with it, more terrible stories and more loss of trust and confidence in policing.”

In response to a request for comment from George V Magazine, the NPCC lead for Violence Against Women and Girls and Deputy CEO of the College of Policing DCC Maggie Blyth stated that while progress has been made, “change hasn’t been quick enough, and much more needs to be done to ensure women and girls feel safe.”

She assured that policing is working to “root out those not fit to wear the uniform” and foster a culture that calls out misogyny. She emphasised the need for officers to be “upstanders, not bystanders,” and committed to implementing changes through the College of Policing’s new framework for 2024-2027.

*Names and some details have been changed to protect victims and survivors’ identities and safety.

Refuge’s National Domestic Abuse Helpline 0808 2000 247, available 24 hours a day 7 days a week for free, confidential specialist support. Or visit www.nationaldahelpline.org.uk to fill in a webform and request a safe time to be contacted or to access live chat (live chat available 3pm-10pm, Monday to Friday). For support with tech abuse visit refugetechsafety.org.

For more information about reporting and recovering from rape and sexual abuse, you can contact Rape Crisis on 0808 500 2222.

If you have been sexually assaulted, you can find your nearest Sexual Assault Referral Centre here. You can also find support at your local GP, voluntary organisations such as Rape Crisis, Women’s Aid, and Victim Support, and you can report it to the police (if you choose) here.

Change