|

Neubauer Coporation

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

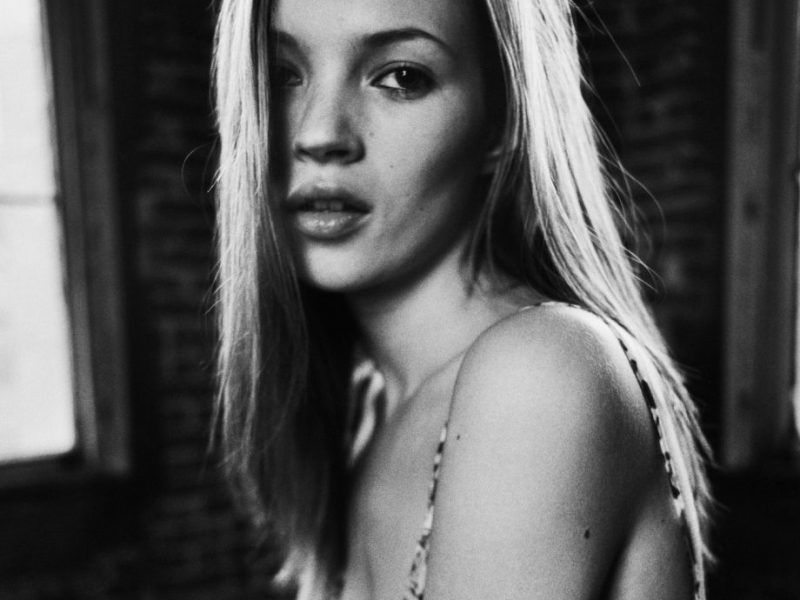

He is the man who captured everyone from Kate Moss to Nelson Mandela. The man who missed images of icons due to his Protestant upbringing, so decided to make them himself. Anton Corbijn, world-famous photographer and director, but also that boy from the Hoeksche Waard, is now exhibiting with MOØDe in the Amstelveen Cobra Museum.

Anton Corbijn (68) wants to meet at the Westerpark in Amsterdam for his interview with Vogue. That’s handy, I hear later: his studio is nearby. It’s just before half past two in the afternoon. I’m a bit early, order a ginger tea and stare out the window. It is raining harder by the second, but I was spared the downpour. Just when it starts to storm harder outside, a man comes in. A gust of wind fills the cafe. He has a soft yellow beanie on his head, wears a dark blue sweater and striped sweatpants. He turns and scans the room.

Interview Anton Corbijn

Corbijn, somewhat shy, but with a winning smile, shakes my hand and takes a seat. He takes off his hat. In the autumn light his hair appears silver. I compliment his pants. “It’s beautiful, isn’t it? Since I’ve been with my wife Nimi (Ponnudurai ed.), I pay more attention to what I wear: she is a big fashion lover. This one is by Dries Van Noten, my favorite designer,” he says proudly.

He orders a jasmine tea, says he is doing well and that he is flying to Rome tomorrow for a shoot. While his peers are starting a well-deserved retirement, he has no intention of stopping just yet. That is not surprising: Anna Wintour herself asked Corbijn – as he often does – to photograph for American Vogue in the Italian capital. Do you ever get used to those kinds of requests? “Yes,” he says wholeheartedly. “You can get used to everything.”

Love for photography

Corbijn was born in Strijen: a village on the South Dutch island of Hoeksche Waard. It’s green. There isn’t much more than that green. You can canoe there, lie in the tall grass of the many meadows, and swim. His father is a pastor, and the family goes to the Protestant church every Sunday. Inside it is white and sober: images of icons are missing, as befits the Protestant church. There are black suits and top hats. Corbijn is a quiet boy in the village, almost shy. He is not the best at school, he has no idea what he wants to study. But it is certain that he does not want to become a pastor or doctor like the rest of his family. Just like the feeling he has carried with him for years: a longing for freedom, far away from that island on the water.

In the 1970s, the Corbijn family moved to Groningen for their father’s work. Not much later, a band plays on the Grote Markt that Corbijn wants to see, but he doesn’t know anyone in the city yet to accompany him. So he comes up with another plan. “I was too shy to go on my own. Until I thought of taking my father’s old camera with me. That gave me something to do, I got something to hold on to.” Corbijn shoots some images of the performance and sends them to a music magazine. They are placed – pro bono, yes, but his images are in a magazine. With his name added. “That felt fantastic. I slowly became more and more part of that free world.” At that moment, while taking pictures with his father’s camera, something clicks in Corbijn’s ever-racing head. He has found his calling.

Own style

The year that follows is characteristic for the young photographer. After shooting some concerts, Corbijn starts to be disturbed by the environment: the rays of the neon light fly in all directions, musicians jump around on stage. There is no control. He wants to become the boss of his work by staging his photos. “I wanted to make more portraits, decide for myself how someone should stand, what the light should be, whether I wanted to shoot outside or inside. I wanted to recreate the pictures that were in my head. So I did that.”

He shoots and shoots, rolls full. During the following summer holidays – he has now obtained his high school diploma – Corbijn raises enough money from his summer job at Friesche Vlag to buy his first camera. During the same period he tries to enter an art academy. “I sent my work to three different schools. Nobody wanted me. I thought that was terrible at the time, but afterwards I am very grateful that I was refused,” he says with a smile. “It’s ultimately the best thing that happened to me. This way I have been able to follow my own path and learn to make what I like. People say I have my own style, but that’s mainly because I don’t know how to do it differently. I make images that I want to see myself.”

Privately

Corbijn starts making the portraits for which he is now so famous. They are black and white, have a coarse grain, and are made on location instead of in a stark white studio. His subjects are different every time, but they all share a vulnerable side of themselves in the images. You see it in their eyes, the way they stand. Corbijn thinks it’s clever, especially because he finds it difficult to be vulnerable.

He is careful with what he shares. Probably due to his Protestant upbringing. “I think so, yes. I’m not that open,” he agrees. “It’s very important to me to have a private life. That’s mine, not everyone’s. What I want to share with people is my work. No more.” Does that make him find interviews like this uncomfortable? Laughing: “If there are questions I don’t want to answer, I’ll find a way to get out of it.”